Luke Bemish

An undergraduate studying mathematics and biology with a concentration in neuroscience; interested in systems neuroscience and dynamical systems.

Version Control Software: What, Why, and How

by Luke Bemish

- Why use version control?

- How does version control work?

- What is version control software not?

- General setup

- Sharing code

- Integrating git with other tools

- Further Reading

Whether a student or researcher, one will inevitably need to make multiple iterations of code while developing tools for data analysis, experiment control, modeling, or any of the other many situations where software is necessary for research. Tools known as version control software, or VCS, can help keep track of the iterative development of a tool over time. Version control software allows researchers to share both the original iteration of software as used in a publication, alongside any further improvements or changes made to the software since publication.

Why use version control?

Using version control software offers several advantages. First, keeping track of multiple iterations of code allows for better experiment reproducibility - it is possible to easily record the state code used to run an experiment or analysis alongside the data itself. Additionally, version control allows for safer development of software; using this software can make reverting code to an earlier version, or selectively using only some parts of a broken, newer version, much easier. Furthermore, version control makes development of tools easier when multiple people are working on the same project; it can reconcile and merge changes made to the same code by different people at the same time. Version control also makes it easy to share tools between multiple people or multiple computers, and ensure that everyone is working with the same code. Finally, many version control software tools allow code to be backed up in the cloud for free, helping ensure that code will not be lost if local computers catastrophically fail.

Version control software offers advantages when sharing code at publication and beyond as well; code can be made publicly accessible, and those using it can offer to contribute features or fixes back into the software itself, allowing tools to continue to have use and evolve long after their initial development.

How does version control work?

One of the most common tools used for version control is known as “git”. Though I will use the terminology used for git specifically here, many of the concepts apply to other version control tools as well. Version control centers around a “repository”. A repository is, fundamentally, just a folder with code in it; version control software is responsible for tracking changes made to code within this folder, and, when you tell it to, writing those changes to an internal log; each recorded set of changes is known as a “commit”. A local repository is the folder that exists on your computer; most often, this local repository will be linked to a remote repository, which is stored in the cloud. A common tool for hosting remote repositories is GitHub.

Generally speaking, there are a number of interfaces with which you can interact with git. While some people enter commands in a terminal to control git, these commands can take some practice to get used to, and often require frequent trips to the documentation. Additionally, many common tools for developing software contain built-in integration with git. I will outline how to set up git and GitHub for a number of different scenarios.

What is version control software not?

Version control software is meant primarily to handle code; using it to keep track of or back up data is not recommended. In fact, many of the tools used for version control struggle to deal with large files, and may end up using more disk space or taking longer to record changes when the files being used are too large. It is generally a good idea, for this reason, to store data in a different location than your code; for instance, you might have a subdirectory where all of your data is stored named data, and tell not to track files in that folder - later, I will discuss how to use a .gitignore file to accomplish this. Journals will likely have their own guidelines for how supplemental data should be distributed, and specific guidelines for hosting it.

General setup

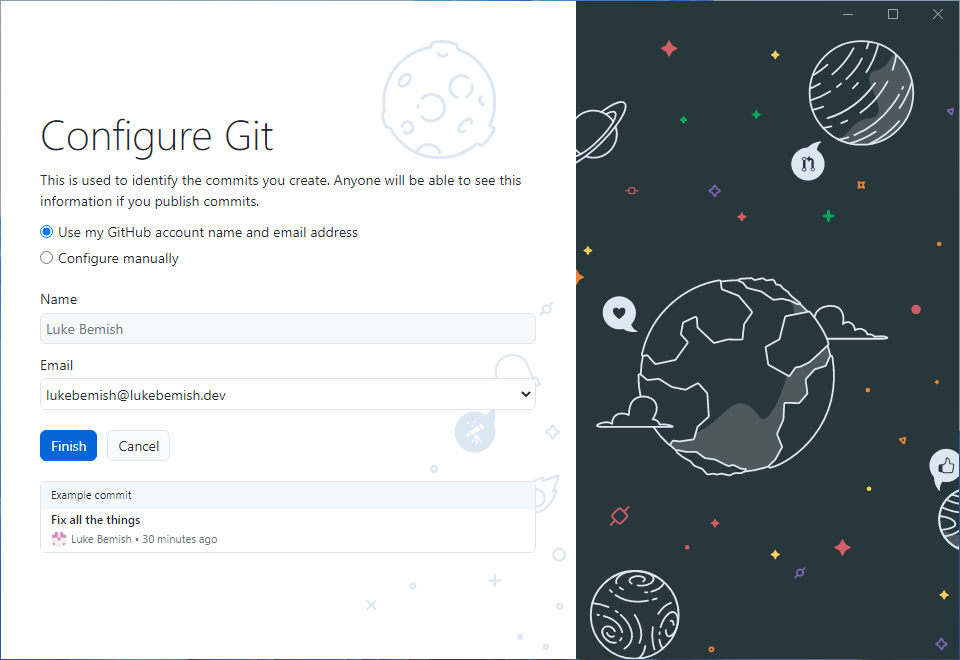

To set up your first repository, you will want to make an account on GitHub, install GitHub Desktop, and sign in with your GitHub account:

After signing in, you will be presented with a screen where you can make new repositories, or add existing folders as a repository; these options can always be accessed later through “File → New Repository”. You can also make a repository online, from GitHub, and then “clone” it to GitHub desktop - copying the remote code to your machine. This is useful for sharing code between multiple people with different computers - each person can have a local copy of the code on their machine.

When making a new repository, you will be able to choose a name and a description for the project, as well as, optionally, a “git ignore”. A git ignore (stored in a file named .gitignore) is a file which tells git which files not to keep track of. This can be useful when a project contains files that are generated separately on different machines, or that should not be stored alongside code. Common examples of uses of a .gitignore file are data folders, or files such as .pycache files generated by python. GitHub Desktop contains several useful .gitignore templates for commonly used languages, such as R and Python. Each line of a .gitignore file holds a different pattern for files to include; some common patterns you might see include:

*.pyc,*.asv, or similar - ignores files with a specific extension.ipynb_checkpoints/,data/or similar - ignores files in a given directory

For more information, see https://git-scm.com/docs/gitignore.

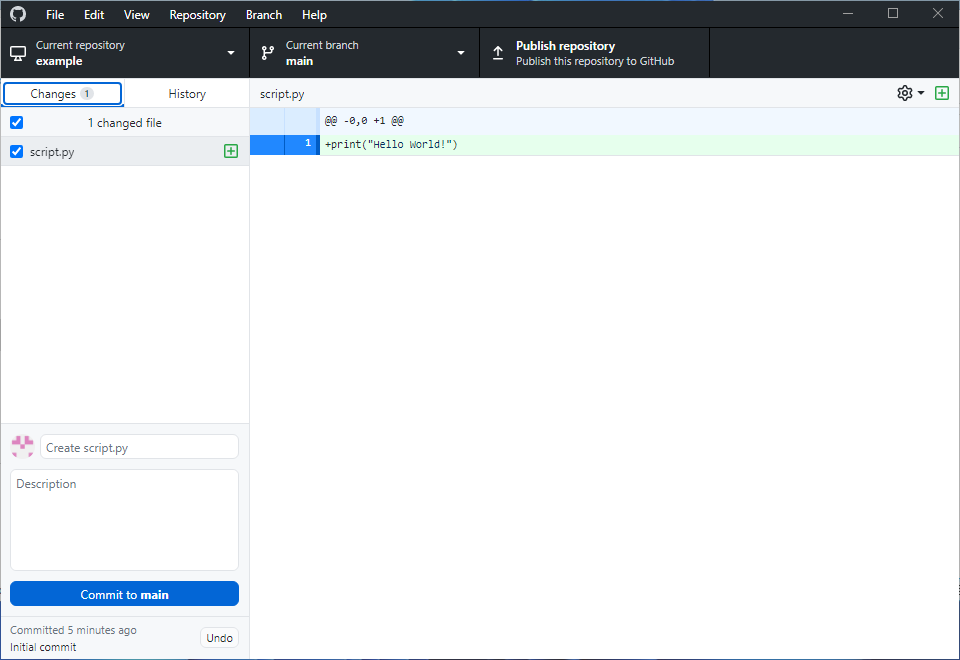

Once you have made a set of changes to code that you would like to track, your window should look something like this:

You can use the checkmarks and the pane on the right to select which changes you want to keep track of together - in a single “commit”. Then, you can give the commit a title and description; these titles will be one of the easiest ways to search for specific changes you made after the fact, so it is important that they be descriptive. When pressing “Commit to main”, git will add those changes in one commit to the “main” branch of your repository. Branches are one of the ways that git can keep track of the same code with different sets of changes applied to them; you can make different sets of changes to code in two different branches, easily switch which branch you have currently on your local computer, and even merge branches back together and combine code from both. Once you have committed your changes, you will be able to press “publish repository” (or “push origin” once you’ve published the repository the first time) to add your local changes back to the copy of the code kept in the cloud; at this point you will also be given the option to keep the code public or private.

Before committing any changes, it is always smart to press “fetch origin” (which will be in the same place as the “push origin” or “publish repository” button) - this checks the code stored in the cloud for any changes made there since last you updated the local code. If there are changes remotely not present on your computer (for instance, perhaps you updated the code from a different computer), then you can press “pull origin” to download those changes. Occasionally, the changes in the remote code will affect the same lines as the changes in the local code, and so will not be compatible; in that case, you have what is known as a “merge conflict” and will have to manually edit the files involved to resolve the conflict.

Sharing code

A git repository can be shared with others in several ways. The simplest is to simply add others as collaborators on the repository on GitHub. This can be done under the “Collaborators” section of the repository settings on the GitHub website. All collaborators will have the same access to a repository, and will be able to check out the code locally and push their changes back to the same GitHub repository, even if the repository is private

The second option is to make a GitHub organization. This can be convenient when the same people need to work on many different repositories together; the people can be added to the organization, and will then have access to the repositories owned by that organization. Organizations are similar to users on GitHub, and can do much of the same things that users can; the major difference is that organizations can have members, and give them access to repositories. Organizations have many features that can be useful as the number of people working on a project grows; for instance, different people can be given access to different repositories within an organization, or have different levels of permission within a single repository.

The third, and possibly simplest, way to collaborate with GitHub is simply to make the repository public. If your code is public already, this type of sharing might already be set up. This is most useful when parts of a wider community work with your code; somebody with their own fix or improvement can “fork” the repository, making their own copy of it which they can edit without affecting the original. Then, if they choose, they can create a “pull request”, which will ask the owners of the original repository to merge the changes they made to their copy back into the original project. Pull requests can also be used within a single repository, to merge changes made on one branch into another.

Integrating git with other tools

While you can certainly use GitHub desktop on its own to manage your repositories, several common tools for scientific computing also have support for git. For integration with other software, you will likely also need to install the standalone binary version of git, which, unlike the version used by GitHub Desktop, can be accessed from the command line; versions for many operating systems can be found on the git downloads page. If you have two-factor authentication set up for your GitHub account, the GitHub CLI tool may make logging in easier; simply download it following the installation instructions and run the command gh auth login.

Matlab

MATLAB has built-in integration for git, allowing you to commit files from within MATLAB. For instructions in setting it up, see https://www.mathworks.com/help/matlab/matlab_prog/use-git-in-matlab.html.

RStudio

RStudio has built-in integration with git, and GitHub Desktop has built in integration with RStudio. In GitHub Desktop, “Repository → Open in RStudio” allows you to open a repository in RStudio. From RStudio, you should be able to control git through the “Git” pane. RStudio also automatically creates a .gitignore file when making a new project.

JupyterLab

If you use JupyterLab, you can install the jupyterlab-git extension to add support for git.

Many other common tools for developing scientific software will have some form of git integration built in; additionally, many other dedicated tools for working with git exist besides GitHub Desktop. For a list of some of the most popular ones, see https://git-scm.com/downloads/guis.

Further Reading

Here, I have barely touched the surface of what git (and GitHub) have to offer. GitHub’s documentation offers a wealth of resources on how to do various operations with git, such as making “releases” that mark the state of code in a repository at a given time for an easily rememberable name, offering to contribute fixes or features back to public repositories, and more. Git is an incredibly powerful tool, and its use can help software stay organized and lead to reproducible results, and I hope that you will find it useful.

Have questions or thoughts? Feel free to reach out to me at [email protected]